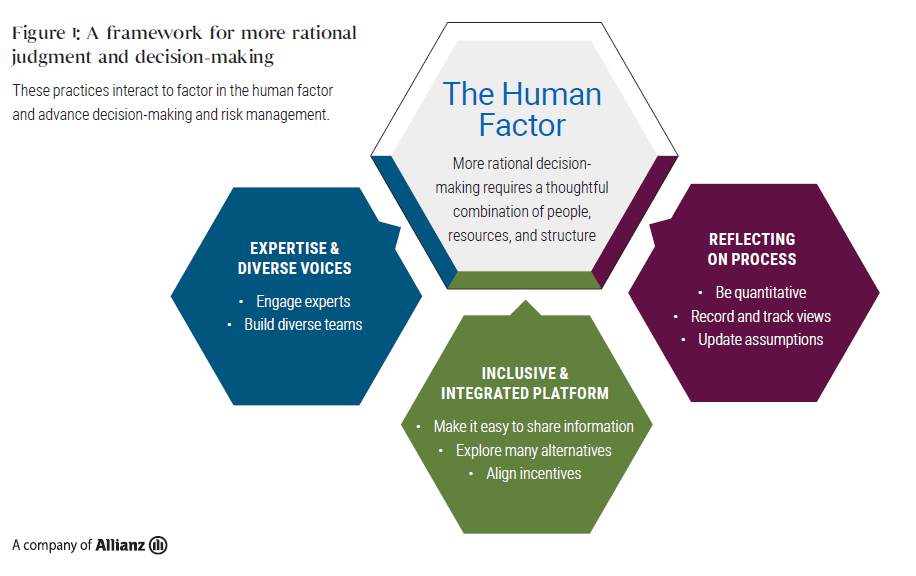

The Human Factor: Using Behavioral Science to Improve Investment Decisions

- PIMCO seeks a competitive edge by using behavioral science to advance rational decision-making and risk management.

- The process relies on a diverse workforce that shares ideas and constructs innovative investment strategies.

- We spur collaboration by structuring processes and interactions to promote inclusive information-sharing and reduce biasing noise.

- It’s essential to constantly monitor and improve these practices in a disciplined, data-aware, and long-term process.

Sound investment management requires a constant effort to test, challenge, and improve the processes that underpin investment decisions. Accounting for human factors has become central to the effort.

As a steward of our clients’ capital, PIMCO has long sought to develop and reinforce a framework for more rational decision-making. It’s an effort that continues to evolve. Behavioral science insights can improve practices to collect and combine information that informs investment choices. Key to the effort is hiring people with a wide variety of experiences and perspectives, and structuring teams and workplaces to maximize the interchange of ideas, challenge assumptions, and reduce cognitive bias errors.

This piece shares practices drawn from behavioral science that can be used in a variety of institutional scenarios. We will illustrate with examples of how PIMCO applies them to mitigate risk, optimize judgment and decision-making, and provide a critical edge in our investment process.

Expertise and diverse voices

More intentional, conscious talent composition is a key to establishing a framework for better decision-making processes and outcomes. It starts with domain experts – think of Navy SEALs, paramedics, and chess masters – who have acquired sufficient training and experience to process information instinctively and respond automatically.

Specialists have uniquely informed perspectives, developed through extensive research and feedback, that helps them catch what others miss, since they know more about what to look for and expect. This is why it’s essential to seek input from as many experts as possible, but also be mindful to avoid both too much overlap and too little coverage in their domains, methods, and backgrounds.

How PIMCO puts this into practice:

- We get input from many of the world’s leading experts for advice on the economic and political landscape. These include PIMCO’s Global Advisory Board , whose members include:

- Ben Bernanke, former Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve from February 2006 through January 2014

- Joshua Bolten, CEO of the Business Roundtable and former White House Chief of Staff

- Gordon Brown, former U.K. prime minister

- Mark Carney, UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance and former Governor of the Bank of Canada and the Bank of England

- Michèle Flournoy, former U.S. Under Secretary of Defense for Policy

- Ng Kok Song, former Group CIO of the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation - Richard Thaler joined PIMCO as a senior advisor in 2019. He is a professor of economics and behavioral science at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, a pioneer in the fields of behavioral economics, and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 2017.

- These and other distinguished thought leaders from academia, business, and government participate in PIMCO’s Cyclical and Secular Forums – where the firm gathers to debate and discuss the investment outlook over different time horizons – and in meetings of the Investment Committee (IC) to share information and shape and challenge the firm’s views.

- We draw from an extensive pool of internal specialists who validate and contribute evidence within cross-divisional working groups, breaking down and addressing specific components of any situation.PIMCO has 14 sector specialty desks, a dedicated team of economists, over 45 Ph.D.s in a variety of fields, more than 240 chartered financial analysts (CFAs), and more than 290 portfolio managers (PMs) with an average of 17 years of investment experience.

Of course, experts are not the only people with unique and highly valuable perspectives. Macro strategists and investments professionals (IPs) help synthesize insights and create multisector strategies and integrated portfolios. Similarly, strategies and results can be more relevant and innovative when there is input from a diverse composition of team members, with individuals who bring knowledge, skills, and perspectives from a variety of backgrounds, cultures, attitudes, networks, identities, and demographics.

How PIMCO puts this into practice:

- We are expanding talent acquisition by using strategies and technology for more mindful and fair recruiting and evaluations. This includes timely bias reminders and guides, using language-inclusivity software to form gender-neutral job ads, and expanding where they are posted. In addition, to find talent from underrepresented groups, PIMCO participates in the Career Exploration Program and Summer Intern Program and also funds the PIMCO Future Leaders Scholarship .

- We value a global mindset. For example, our four regional portfolio committees (Asia-Pacific, Europe, the Americas, and Emerging Markets) have members who live in the region; we also encourage movement of employees across our 22 offices.

- We form heterogeneous teams, in part to give junior investment professionals (IPs) opportunities and experiences, and to balance inputs for individuals accountable for making the final decision.

The benefits – A deep and diverse bench of talent has more complete information and more precise assumptions. Moreover, over time, regular exposure to diverse perspectives can improve the way humans process information. Using the terms from psychologist Daniel Kahneman’s book “Thinking Fast and Slow,” the exposure stimulates analytical and systematic thinking (“slow” processes), such as reflection, hypothetical reasoning, and doubt. And sustained use of these processes works to improve “fast” thinking processes, too, by training an intuitive response to be a more logical one.

These practices can help override automatic oversimplifications, such as confirmation bias and stereotyping. They also can help mitigate cognitive bias errors related to group conformity by instilling more individual responsibility and generating fresh ideas.

Expertise enhances our ability to customize strategies and solutions to seek value in unique and special situations. It also improves our economic forecasting.

Additionally, these practices help expand personal awareness and recognition of one’s own biases (such as blind-spot bias and overconfidence), and mitigate the tendency to project personal preferences onto others (the false consensus effect).

Glossary terms:

- Thinking Fast and Slow = Dual processing: Human cognition (thinking) relies on two complementary sets of processes (Systems 1 & 2) both of which are rational and work as a team to make judgments and decisions.

- “Fast” Thinking Processes = System 1 thinking processes are automatic, spontaneous, and unconscious, such as heuristics, associations, intuition, emotions, and experiential “gut” feelings. S1 processes can account for upwards of 95% of thinking.

- “Slow” Thinking Processes = In contrast, System 2 processes are effortful and deliberate, conscious and controlled, and serial and fine-grained; including, analytical reasoning, reflection, doubt, hypothetical reasoning, mental simulation, and abstraction.

- Confirmation Bias = Requiring less information to reach a preferred conclusion, and searching for and unreservedly accepting confirmatory information while quickly dismissing or explaining away disconfirming information.

- Stereotyping = Assuming that a fixed, overgeneralized belief about a group applies to individuals perceived as members of that group.

- Group Conformity = When individuals yield to the majority’s beliefs and opinions because there is desire or pressure for harmony and cohesiveness, which can result in inaccurate and irrational group judgments, decisions, and behaviors.

- Blind-Spot Bias = Assuming that judgment and decision-making biases don’t affect the self as much as they affect other individuals.

- Overconfidence Bias = When an individual or group overestimates their abilities or knowledge.

- False Consensus Effect = Assuming that one’s personal preference is a universal or dominant preference among others as well.

An inclusive and integrated platform

After bringing together these diverse sources of talent and information, the next collection of practices focuses on structuring work environments to make it easy to share information among people and across domains. The power of the environment in determining behavior too often goes unrecognized or undervalued, but situational constraints can limit even the most talented teams.

Behavioral science research can identify at least three main practices to better enable the interchange of ideas. First, make it easy to connect and share by leveraging contextual factors such as proximity, salience, formality, and frequency. In less technical terms, this means providing ample opportunity to communicate via events, surveys, polls, technology (e.g., apps, microphones, and cameras), and office working styles (e.g., transparent walls and shared working spaces for certain functions; time alone for individuals to brainstorm).

However, physical changes alone are not sufficient. We’ve learned that more discussion doesn’t necessarily yield more knowledge. So the second step is to create a culture that helps colleagues feel comfortable sharing constructive feedback and unique insights. Better practices encourage teams to systematically explore the potential of many different options and solutions and evaluate challenges through a variety of frames and perspectives.

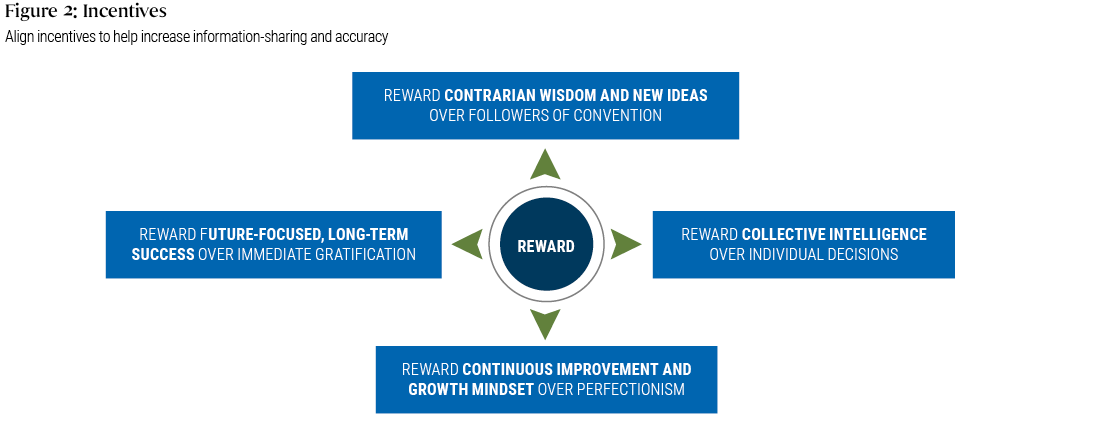

The third step requires providing proper incentives. Many profitable outcomes arise when people at all levels speak up, point out mistakes and assumptions, and back up their positions with research and evidence. It’s challenging to prevent social politics from affecting behavior, and incentives provide a crucial component. For example, incentivizing employees to hold a mindset of continuous improvement and growth encourages teams to look for and correct more mistakes.

The best ideas review process

PIMCO regularly conducts a Best Ideas exercise in which our IPs submit their top three investment ideas. Submissions are anonymous to minimize the influence of factors aside from strength of the evidence and arguments. Knowing who is responsible for an idea can create a halo (or horns) bias, where the reviewer’s positive (or negative) perceptions of an individual’s personality change whether and how they evaluate the idea. Moreover, removing the influence of a potentially biasing input, such as a person’s status or gender, after an evaluator’s impression of the idea already has been formed in the brain, is about as easy as pulling out sugar that has been stirred into a cup of hot coffee.

Great ideas can come from anywhere, and anonymity improves the chances that the best ones are elevated before biases take root. As an incentive, unique pitches and critiques are rewarded with more attention from the Investment Committee.

How PIMCO puts this into practice:

- Leaders and IPs receive inclusivity training and make a conscious effort to be approachable and encourage participation in discussions. For example, leaders account for status and presentation order by waiting for others to share views before revealing their own.

- We work to identify and account for supposedly irrelevant factors (i.e., biasing inputs). For example, being more mindful of default options and formats, such as how information is being presented in meetings and forum discussions, to avoid unintentionally restricting or highlighting information (anchoring and adjustment bias) with any single type of template.

- We seek out feedback. Risk management teams confer with other internal teams to challenge assumptions and assess material with a fresh pair of eyes. On the trade floor, we publish performance metrics daily; we review them at regular intervals, examining recent performance in both shorter- and longer-term contexts.

The benefits – These practices focus on connecting the right people with the right information at the right time, to ensure that choices are appropriate to meet even the most novel client needs.

Thoughtfully combining talent and environmental factors better enables colleagues to provide information and critique ideas consistent with their merits. As a result, groups are more likely to poke holes in judgment and decision-making illusions – such as the planning fallacy, framing effects, overconfidence and illusory correlation – by identifying arguments that are inconsistent, incomplete, not repeatable, and not feasible.

Workplace processes can be optimized for inclusive communication by implementing strategically timed reminders and nudges (channel factors) to guard against behavioral biases and informational noise. In short, practices aim to make the desired behavior (e.g., knowledge-sharing) the easier option as well. This can reduce error by making better use of people’s natural reliance on heuristics, like the availability bias, by designing spaces where these mental shortcuts are more functional. More efficient systems also make it easier to navigate complexity, identify opportunity, innovate, and launch new solutions.

Glossary terms:

- Halo (or Horns) Bias = Using one or very few positive (negative) characteristics, personality traits, or experiences from a person to justify positive (negative) assumptions about their broader character and contributions.

- Supposedly Irrelevant Factors = Information of a relevant factor (i.e., judgment and decision-making inputs) that people do not recognize is influencing decisions and behavior.

- Anchoring and Adjustment Bias = People tend to overweight the first piece of information over subsequent pieces, even when the first piece of information is irrelevant or inaccurate. This bias comes from over-applying a heuristic that says past events can help predict/estimate future events.

- Planning Fallacy = Underestimating how long or difficult it could be to complete a future project.

- Framing Effects = Emphasizing the positive values (e.g., gains, returns, rewards, benefits, saving, discounts) vs. the negative (e.g., losses, penalties, withdrawals, withholdings, fees, expiration) of an investment prospect can lead people to make inconsistent decisions — conservative vs. risk seeking, respectively — even though the outcomes are actually equal.

- Illusory Correlation = Misperceiving an association between two factors that are unrelated.

- Channel Factors = External judgment and decision-making inputs that make choices/behaviors either easier or harder. For example, a nudge is when channel factors make a welfare-promoting (prosocial) option the easier choice (e.g., removing barriers or adding incentives), while sludge is when channel factors make it harder to choose a welfare-promoting option (e.g., adding barriers).

- Heuristics = Decision-making shortcuts or simplified formulas for broad application. Heuristics tend to make a trade-off between effort and accuracy. That is, they are fast, free, and sufficient but may not be the most optimal. As a result, heuristics are not irrational, but they can lead to systematic errors, biases, and illusions.

- Availability Bias = A heuristic that says if something is easier to remember, then it’s also more common. The problem is that frequency is not the only factor that can make something easy to recall. In fact, it may be due to the opposite reason — things that are extreme, vivid, recent, or negative are also more memorable. Over-applying this heuristic becomes a bias that increases error.

Reflecting on process

A final collection of practices focuses on being more deliberate and measured in processes. First, a quantitative approach is essential. Constructing models and procedures is a systematic, disciplined endeavor that requires original research, analysis, and numerical evidence; they entail specific assumptions and rationales; and they must offer detailed and transparent documentation.

How PIMCO puts this into practice:

- The client solutions and analytics teams (comprised of over 110 solutions strategists, quantitative researchers, and technologists) conduct thousands of customized, independent studies to help clients design portfolios in light of their investment objectives and constraints.

- Economists and IPs use data-driven techniques to estimate the likelihood of market events (such as recessions), anticipate the course of monetary policy, and quantify financial conditions.

- We support quantitative technology companies (such as Beacon and Hub ) through strategically transformative partnerships and investments. These can deliver high-quality financial research and tools and improve valuation models and risk analytics.

- Using machine learning approaches such as artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms allows us to analyze exponentially larger data samples, refine and expand predictive models, and augment our process with new types of data and analyses.

Reflecting on process also focuses on regular beta-testing, stress-testing, iterating, and updating. This means developing a risk-management plan with quantified ex ante (forecasted) guideposts and check points, and then pausing often to record mental states, assess performance, and adjust.

Then the goal is to use the outcomes – positive and negative alike – as feedback. This can help to identify the drivers of performance; to verify and update forecasted and actual portfolio construction assumptions, models, and procedures; and to improve the accuracy of hypotheses and forecasts.

These practices are useful for two reasons. First, because processes are often repeated, it’s valuable to learn and improve each time. Even when we are correct, it’s important to verify the reason. Second, these practices are forward-looking, situating the present into broader, longer-term economic trends.

How PIMCO puts this into practice:

- We host three Cyclical Forums each year to update near-term positions, as well as an annual Secular Forum to review and update views on longer-term trends. This process helps PMs absorb the macroeconomic outlook efficiently while keeping their main focus on portfolio performance.

- We better track Investment Committee perspectives on various risk factors over time, in terms of both overall and individual stances, and use AI algorithms to review and organize communications and forum outlooks – for example, identifying similar time periods (such as inflation in 2011 versus 2021) and comparing issues, arguments, and estimates to ground the present circumstances.

- Professor Richard Thaler introduced PIMCO to premortem exercises, which the firm applies in forum settings and in the Americas Portfolio Committee (APC). Premortems work to widen minds to additional possibilities, including the risk of being wrong and needing to change course, by generating multiple ways that a market or macro event could impact investment performance. These processes help guide portfolio construction by establishing a core base case with a range of scenarios of various likelihoods.

The benefits – Advanced technology and analyses help overcome human limitations like lack of time, resources, effort, and cognitive capacity. Balanced, quantitative systems also reinforce consistency and objectivity. These practices reduce the impacts from probability-based biases like base-rate neglect and the conjunction effect.

Humans are inherently lopsided in the way we collect and combine information – the impulse is to quickly accept evidence that supports preexisting views and criticize or dismiss evidence that violates a preferred conclusion. This can fuel attribution errors, overconfidence, and motivated reasoning biases (such as confirmation bias).

A well-supported, forward-looking perspective can help buffer against noise from irrelevant inputs and unproductive thinking processes, especially those linked to strong emotions like irrational exuberance and regret avoidance. Staying thoughtful and measured makes it easier to remain calm and rational while navigating market volatility, and to head off recency bias and hindsight bias (by not over relying on memory).

In closing, outcomes won’t always play out precisely as predicted. Yet structured, rational judgment and decision-making processes are more likely to lead to the best decision at any given time, providing an edge.

The Human Factor framework was developed through a review of the practice and application of behavioral science within PIMCO, including conversations with firm leaders across portfolio management, risk management, credit research, analytics, and inclusion and diversity.

Glossary terms:

- Base Rate Neglect = Base-rate information describes the statistical prevalence of a characteristic or event. When judging probability, people tend to ignore or underweight the general commonness of the characteristic or event while determining what is likely in the current case.

- Conjunction Effect = A misperception that two separate things happening at the same time is more likely than just one of those things occurring.

- Attribution Errors = Attributions aim to answer the question “Why did that happen?” And an attribution error means that the proposed explanation (“it happened because…”) is incorrect.

- Motivated Reasoning = Forms of thinking that are less open-mind, more wishful, and often unconscious that work to favor a preferred conclusion. Common biases include Confirmation Bias, Selective Exposure (avoiding disconfirming information), Motivated Skepticism (reviewing disconfirming evidence more critically), and Cognitive Dissonance (“mental gymnastics” routines that force consistency or rationalize disconfirming evidence).

- Irrational Exuberance = When strong emotions — such as excitement, envy, hope, and regret — and heuristic thinking (lacking historical analysis & careful deliberation) create a feedback loop that motivates unreserved participation in popular investments.

- Regret Avoidance = Regret is a negative emotion that people seek to avoid, so the risk of anticipated future regret is an input that systematically influences current decision-making, although the direction of that influence depends on the context.

- Recency Bias = An order effect in which more recent events and information are easier to remember and have a greater impact on judgment and decision-making compared to information from farther in the past.

- Hindsight Bias = It’s hard to preserve one’s original mindset before learning the outcome of an event. After the outcome, people misremember and overestimate how predictable it actually was.

PIMCO’s deep commitment to behavioral science is embodied by our partnership with the Center for Decision Research (CDR) at The University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Leaders in their field, CDR researchers are constantly engaged in studies investigating how people form judgements and make decisions. Many of these studies take place at the PIMCO Decision Research Laboratories – facilities on and off The University of Chicago campus that bring behavioral insights to the mainstream by fostering greater engagement with the public.

Learn more at global.pimco.com/pimcolabs .

Disclosures

There is no guarantee that these investment strategies will work under all market conditions or are appropriate for all investors and each investor should evaluate their ability to invest long-term, especially during periods of downturn in the market.

PIMCO as a general matter provides services to qualified institutions, financial intermediaries and institutional investors. Individual investors should contact their own financial professional to determine the most appropriate investment options for their financial situation. This material contains the opinions of the author and such opinions are subject to change without notice. This material has been distributed for informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission. PIMCO is a trademark of Allianz Asset Management of America L.P. in the United States and throughout the world. ©2022, PIMCO.

CMR2022-0627-2259354