Narrative Economics

Regardless of whether they’re true or false, narratives can drive the economy by influencing our decisions about how and where to invest, and how much to spend and save. In his recently published book, Narrative Economics, Robert J. Shiller, Nobel prize winning economist and a specialist in behavioral finance, lays the foundation for a way of understanding how these narratives help propel economic events.1 While the discipline of narrative economics is at a early stage in its development, we think it’s worthwhile to highlight its main concepts to help you better understand how these narratives can have an outsized effect on your investment decisions.

WHAT IS NARRATIVE ECONOMICS?

In 1936, economist John Maynard Keynes used the term “animal spirits” to describe how people’s emotions and instincts influence their economic behavior.2 While this important concept can, to some extent, be gauged through indicators like consumer confidence, this fails to capture the factors behind changes in consumer confidence. Shiller, along with George Akerlof, expanded on Keynes’ concept by exploring the influence of human psychology on the economy in their 2009 book, Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism.3 Since then, Shiller has further developed the theme, becoming a strong advocate of narrative economics, which is the study of how narratives – especially stories of human interest and emotion – go “viral” and ultimately contribute to economic fluctuations.

Importantly, traditional economic approaches tend to focus on the quantitative, being mostly concerned with what can be measured and counted, such as flows of money, interest rates, supply and demand levels and so on. As such, it typically attempts to explain – and predict – trends and disruptions, like recessions, through the relationships between these economic indicators, and the hypothetical multipliers and feedback mechanisms between them. But this somewhat mechanistic view doesn’t tell the full story. Economic actors are also influenced by the stories they hear, read or see. While studying such narratives is not easy, the advent of vast, searchable databases of newsprint and books, and powerful natural language processing make analysis of narratives possible, which can deepen the understanding of economic phenomena beyond the quantitative data.

WHAT MAKES A NARRATIVE GO VIRAL?

For economic narratives to have a large effect, they need to “go viral.” Interestingly, narratives do indeed appear to spread in much the same way as disease. Contagion occurs from person to person through talk, whether in person or through social media. There is also contagion from one news outlet to another. Consequently, the Kermack-McKendrick SIR model, a mathematical theory of epidemics can also be used to understand the “epidemics” of economic narratives. The model divides the population into three compartments: Susceptible, Infected, and Recovered.

Similar to the trajectory of how an epidemic spreads, narratives require sufficient contact, possibly with more than one person, before a “susceptible” person is “infected,” and a person needs to be sufficiently infected to retell the story for contagion to continue. Inaccurate retellings – like mutations of a virus – are less likely to survive. Shiller writes, “Economic narratives follow the same pattern as the spread of disease: a rising number of infected people who spread the narratives for a while, followed by a period of forgetting and falling interest in talking about the narrative.”

HOW DOES THIS APPLY TO ECONOMIC THEORIES?

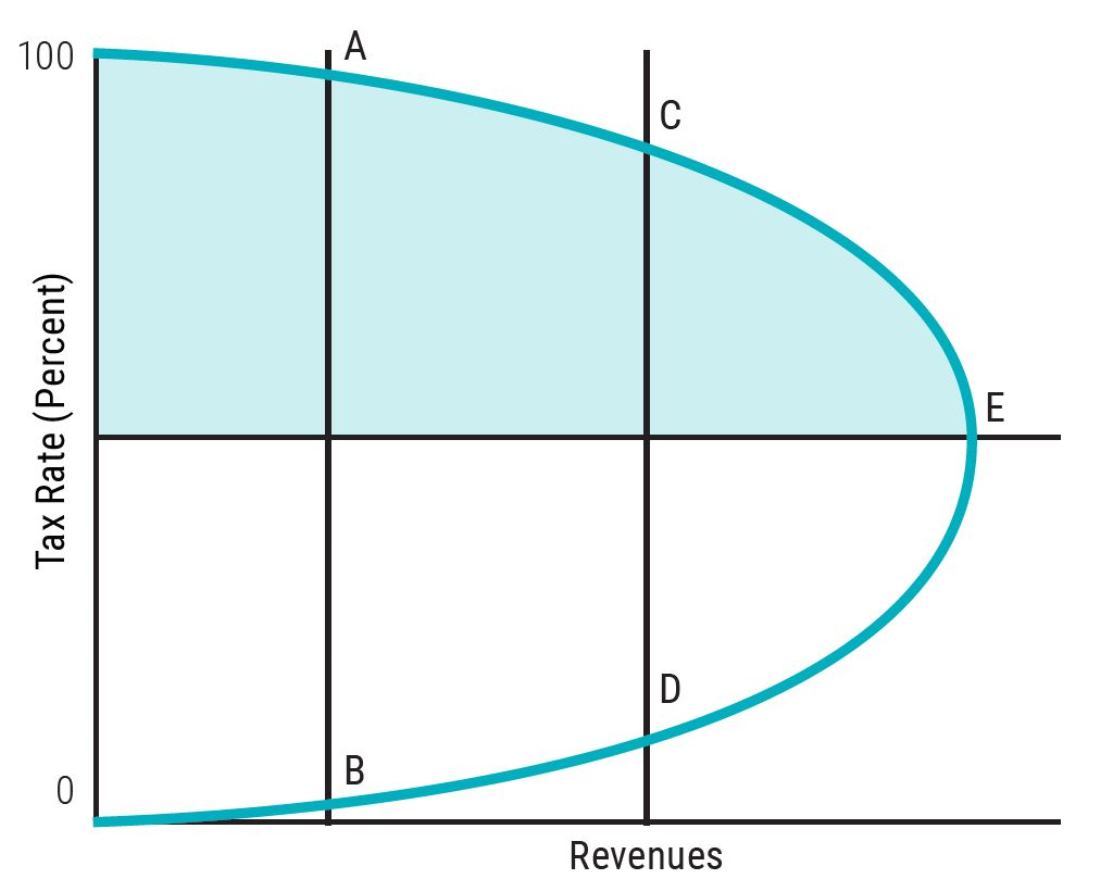

Shiller uses the “Laffer curve” as an example of how an economic narrative went viral to provide insight into how they lead to real world results. The Laffer curve (seen below) is a diagram famously drawn by economist Art Laffer on a napkin at a dinner in 1974 with officials from the Ford Administration to justify the government cutting taxes without cutting expenditures.

While the narrative (and napkin) didn’t go viral initially, four years later, the journalist, Jude Wanniski, who had also been present at the dinner, distilled a very simple and very compelling message from the curve, which was understandable to almost anyone: There are two tax rates that deliver the same amount of revenue: a point C (at a high tax rate), and a point D (at a low tax rate).4 There were no data in the article suggesting that current taxation took place on the high side of the curve, but that was not necessary for the story to spread. The narrative was that the higher one was the “Democratic” tax rate and the lower one the “Republican” tax rate, and that cutting taxes would deliver a huge windfall in national income. Such a powerful explanation of economic inefficiency was contagious enough to go viral.

Wanniski’s telling of the story furthered the narrative’s appeal: The combination of the setting (a restaurant with powerful Washington officials and an academic with a napkin) and a simplistic explanation of something that made sense to many people was enough to kick-start the contagion. And, its contagion, Shiller argues, led to fundamental political changes to economic policy associated with Ronald Reagan, who was elected U.S. president in 1980 and Margaret Thatcher, who had become the UK prime minister a year earlier.

THE LAFFER CURVE

The Laffer curve assumes that no tax revenue is raised at the extreme tax rates of 0% and 100%, and that there is a rate between 0% and 100% that maximizes government taxation revenue.

WHAT ABOUT THE GREAT RECESSION?

Interestingly, the term “Great Recession” itself is evidence of a narrative epidemic. It was first used in relation to the 2007-2009 recession by economist Nouriel Rubini in late 2006,5 but it took another three years before the term finally caught on and went viral. Why? Bank failures, such as collapse of Lehman Brothers, were reminiscent of the Great Depression narrative, as was the huge stock market decline. According to Shiller, “the Great Depression and its causes (after a period of euphoria, loss of confidence) remain a powerful narrative. It was a traumatic period in the nation’s history that is constantly on people’s minds as they listen to other narratives about what will happen next.”

The representativeness heuristic, a mental shortcut that people use when making judgments about the probability of an event under uncertainty – described by behavioral economists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky6 – can be used to understand how the Great Depression narrative became a touch point for the Great Recession. People judge current events by their similarity to memories of previous, representative events. Even though there were many differences, the legend of the Great Depression contained a few strong similarities, and was ready to be adopted for the role, especially as policymakers invoked it to justify their requests to apply stimulus

ECONOMIC NARRATIVES AND BEHAVIORAL BIASES

Economic narratives can be linked to several behavioral biases and heuristics. The representativeness heuristic, mentioned above, is one that investors should be aware of, the framing effect is another. Framing occurs when we make a decision based on the way information is presented, or framed, rather than on the facts themselves. Economic narratives – whether it’s that tech stocks can only go up, housing prices never fall, or that some firms are too big to fail – are examples of framing that can impact investment decisions.

The affect heuristic can also help explain how economic narratives go viral. The affect heuristic is a mental shortcut where people who are experiencing strong emotions, such as fear, tend to extend those feelings to unrelated events. We tend to fall back on the affect heuristic while judging the risks and benefits of something, depending on the positive or negative feelings that we associate with it. Shiller’s joint research with William Goetzmann, Dasol Kim and George Akerlof in 2016 found that people generally exaggerated the risk of a stock market crash, influenced by news stories, especially those on the front page.7 Interestingly, the research also found that stories about natural disasters like earthquakes in their vicinity triggered the affect heuristic, causing respondents to assign a significantly higher probability to a stock market crash.

We tend to construct our own narratives from the movement of hard economic indicators and the corresponding expert commentary. These then influence our investment decisions through an array of behavioral biases and heuristics. But economic narratives can play a special role, because they speak directly to our instincts and emotions. Whether they are true or false, that means they can be profoundly convincing.

Ultimately, it’s important to understand that economic narratives can also influence your investment decisions, for better or worse. Keeping your long-term financial objectives at the forefront of your investment strategy can help you make decisions that are best suited to your goals, regardless of what’s going viral.

BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE IN ACTION

PIMCO has long understood that behavioral science can make us better investors. That’s why we’ve partnered with some of the best minds in the field at the Center for Decision Research at The University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Through this innovative partnership, PIMCO supports diverse and robust academic research that contributes to a deeper understanding ofhuman behavior and decision-making. Learn more about how behavioral science can make you a better investor.

LEARN MORE

Disclosures

This material has been distributed for informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission. PIMCO is a trademark of Allianz Asset Management of America L.P. in the United States and throughout the world. ©2019, PIMCO.

CMR2019-1007-418110